Introduction

Hydraulic was a house, plantation, and a millworks about five miles north of Charlottesville, at the junction of Ivy Creek and the South Fork of the Rivanna River (Fig. 1). From 1829 to 1860 Hydraulic was owned by Nathaniel Burnley (1786-1860), who was a saddler and tavernkeeper at Stony Point for some years before purchasing the Hydraulic Mills. By the time of his death, Burnley owned more than 800 acres, including the Rio Mills further down the Rivanna. At the Hydraulic and Rio sites were grain and lumber mills, blacksmith and cooper’s shops, and stores.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Click here for the entire image.

In this article we will use two examples to demonstrate how to uncover information about African Americans who were enslaved at the Hydraulic Mills. The first example – Thornton Tyler – will start with antebellum records (specifically a Slave List) and move forward in time (“The Path Towards Freedom”). To explore the opposite approach (“Searching for Enslaved Ancestors”): researching someone from a known family and trying to trace their ancestry backwards, visit the Becks Family example. Scroll through the following sections to learn more…..

If you are trying to research African American families who were enslaved on a plantation, the first step is to learn more about the plantation owner, because many of the pertinent antebellum records will be listed under that individual and/or their heirs.

Hydraulic Mills was owned by Nathaniel Burnley. Nathaniel and his wife, Sarah Wood, had nine children, some of whom settled in the Hydraulic neighborhood. Burnley’s uncle Seth Burnley also had large landholdings nearby. The Burnley estate was involved in protracted litigation following the Civil War and the mill was eventually purchased by Rollins Sammons, who had been a free black miller before the war–possibly even Burnley’s miller. Sammons married a great-great-granddaughter of Elizabeth Hemings of Monticello. There are a number of other Hydraulic connections to the African-American families of Monticello.

A vital post-war African-American community grew up near Hydraulic, centered on Union Ridge Baptist Church and a school, which later developed into the Albemarle Training School. The original house at Hydraulic (by then called Redbrook) burned in 1939 and the site of the mills vanished with the creation of the Rivanna Reservoir in 1966.

The Path from Slavery to Freedom

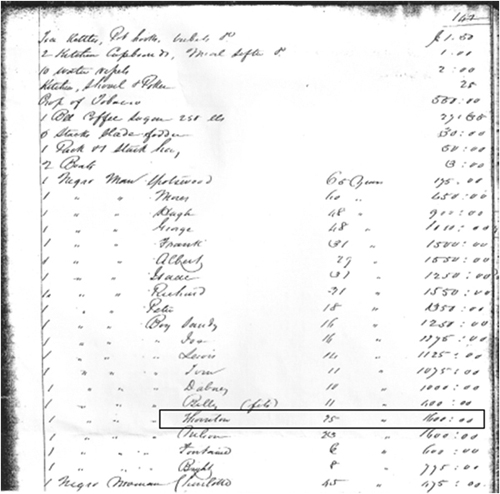

To begin our research into the African Americans who lived in the antebellum neighborhood we began with the Albemarle County Will Books which contain an inventory and appraisal of Nathaniel Burnley’s estate (March 1860) and a record of the estate sale a month later. The inventory listed 39 enslaved men, women, and children; the purchasers of 24 of them are known from the sale record.

–Search for Thornton–

For this search we selected one man from the inventory who was not in the sale (Figure 5):Thornton “Boy” aged 25 valued at $1,600.

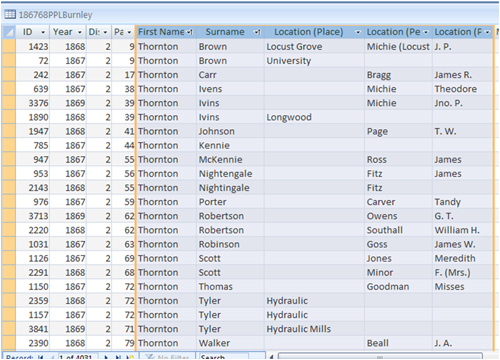

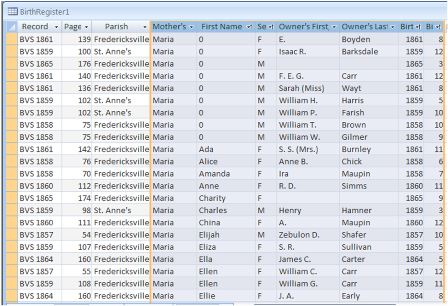

Our next step to locate more information about “Thornton” was to check the Personal Property Tax Lists for 1867-1869. The CVHR group inputted the data from this list, so we turn to an excel spreadsheet where we sort by first name. This resource is particularly helpful because it lists the locations of freedmen for the years 1867 to 1869.

Thornton Tyler is listed at Hydraulic or Hydraulic Mills all 3 years

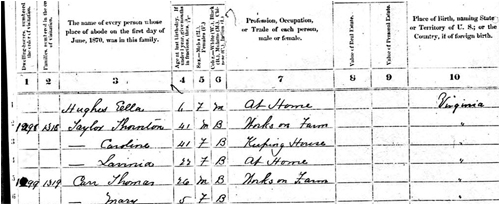

Our third step was to turn to the 1870 Albemarle County Census (the first post-emancipation listing of African Americans). We deliberately selected a somewhat unusual name, “Thornton,” for this example. Thus, we can search the 1870 Albemarle County census by first name to locate possible options. We find a “Thornton” who fits the right criteria. This gives us a surname for a formerly enslaved individual and will make the remainder of our post-bellum searches much easier.

Thornton “Taylor,” age 41, farm laborer, his wife Caroline, and daughter Lavinia appear close to Burnleys (including Nathaniel Burnley’s widow), Sammonses, and the family of Fountain Hughes, whose taped recollections are one of the very few surviving sound recordings of ex-slaves.

Our fourth step is to double check to make certain we have the right person, especially because of the age discrepancy. So we crosscheck by looking at the 1880 census, where he is listed as

“Thornton Tyler”, farmer, and the correct age of 45. His wife Caroline and eight children are listed. They are still clearly in the Hydraulic neighborhood.

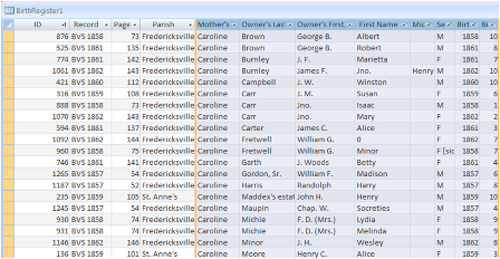

This list is sorted by mother’s name and we are searching for a “Caroline” who fits the criteria to be Thornton Tyler’s wife.

–Who was Caroline Tyler? —

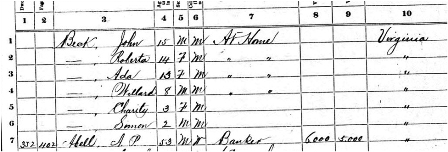

We turn to the birth record database 1857-1866 (Figure 8), sorting by mother’s name. We find,”Caroline,” a slave of James F. Burnley (son of Nathaniel Burnley), appears twice, with children Marietta and John Henry, who match the 1880 census.

Now it is virtually certain that Thornton Tyler and the Thornton on Nathaniel Burnley’s inventory are one and the same. And that his wife, Caroline, belonged to Burnley’s son (and perhaps originally to Burnley).

Now it is possible to gather more details about the family, for example:

- The 1900 census shows the couple still living (in Charlottesville) and reveals that Caroline Tyler bore 15 children, 12 of whom were living in 1900.

- Death records and certificates reveal death dates of several family members as well as Caroline’s maiden name (Johnson).

- Marriage records provide information to continue the family tree.

The Search for Enslaved Ancestors

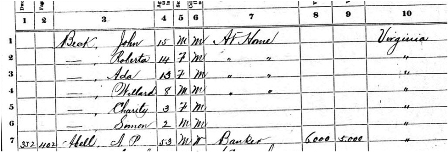

Suppose that someone has traced their ancestry to John and Maria Becks in the 1870 census. They are listed in Fredericksville Parish with six children, John, Roberta, Ada, Willard, Charity, and Simon.

John (age 45) is a gardener, Maria (age 33) is keeping house.

Next we turn to the Birth Record Database 1857-1866 (collected by the Bureau of Vital Statistics). We sort by mother’s name and child’s name and locate a” Maria,” belonging to “Mrs. S. S. Burnley” (i.e. Sarah, widow of Nathaniel Burnley). Maria has a daughter, Ada, born in 1861. This is suggestive but doesn’t quite match John and Maria Becks’s daughter Ada who was recorded in the census as born in about 1857.

So we check the 1880 census, where Ada is 20, within an acceptable range of the 1861 birth record.

The 1870 location of the family is not helpful.

So we check to see where John Becks was immediately after the War. The best source for this information is the Personal Property Tax Lists for 1867-1869. We sort this by last name to locate him. We find a ” John Becks” located at J. P. Railey’s in 1867 and A. J. Craven’s in 1869 (no location given for 1868). Here is another Burnley connection. James P. Railey married a daughter of Sarah and Nathaniel Burnley in 1866.

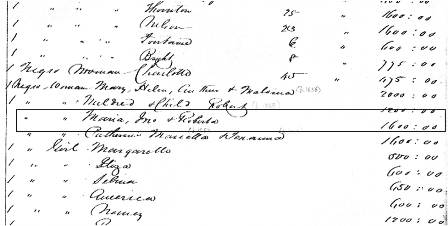

Next we turn to a database that the CVHR is in the process of transcribing: the county Will Book records. We find an Inventory of the estate of Nathaniel Burnley, 1860, which includes “Maria, Jno & Roberta” valued at $1,600. There is no adult John in the inventory. But we do find an unquestionable match with Maria Becks and her two oldest children.

Maria Becks, therefore, was a slave of Nathaniel Burnley. She had an “abroad” marriage with John Becks, enslaved by a different owner.