The Mills

For more than a century, the Hydraulic Mills at the junction of Ivy Creek and the South Fork of the Rivanna River were the commercial hub of a large rural area northwest of Charlottesville. A bustling village grew up around the two grain mills, with a store, a sawmill, blacksmith and cooper’s shops, a wool carding machine, dwellings, and a post office. Grain raised in the surrounding farms and plantations was brought to the mills for processing into flour and cornmeal, and the flour was shipped down the Rivanna to distant markets. Although the mills were plundered by Union soldiers during the Civil War and badly damaged by the great flood of 1870, the millstones continued to grind the grain produced in the local community. In 1872 the African-American miller at Hydraulic, Rollins Sammons, purchased the mills in partnership with a white man, W. W. Worledge. Sammons ran the milling operation into the 1890s. In the twelve months ending in June 1880, the flour and grist mills ground 8,000 bushels of wheat and 6,000 bushels of corn. In 1966, what remained of the village of Hydraulic Mills was flooded by the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir.

After Emancipation

During the hard economic times after the war many large estates were dismantled, including that of the Burnleys, owners of the Hydraulic Mills for forty years. The newly-freed men and women worked to acquire their own farms and banded together to establish their own churches and schools. A vital African-American community—in which members of the Sammons family played a central role—grew up around the commercial center of the mill village. The large farms, like that of Hugh Carr, produced crops of wheat and tobacco, while corn, potatoes, and vegetables were raised on the smaller farms. Almost everyone eventually had an orchard as well as hogs, poultry, and a milk cow, and some had beehives and grapevines. For many, it was necessary to combine farming with work as blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, dressmakers, and teachers. In its extent and importance, this community can be seen as a rural equivalent of Vinegar Hill, the center of post-Emancipation life in Charlottesville.

The Land

The African-American community that grew up around the Hydraulic Mills is a perfect illustration of historian Edward L. Ayers’s statement that “the growth of black land ownership was one of the most remarkable facets of life in the New South.” Freedpeople found ways to acquire pieces of the land on which they had once been enslaved. Some could earn more money through practicing skilled trades or being farm managers. Others worked cooperatively to achieve landownership. In 1868, six men joined forces to purchase a fifty-acre tract near the intersection of present-day Earlysville, Hydraulic, and Rio roads, which they then divided. By 1891 there were almost sixty black landowners in an area that included the interconnected neighborhoods of Georgetown, Webbland, Hydraulic, Union Ridge, Allentown, and Cartersburg. Most had smallholdings of five to ten acres, several owned thirty to eighty acres, and Hugh Carr was the largest landholder with over a hundred acres. The 1930 census demonstrates the steady expansion of black home and farm ownership. See the appended maps for a graphic representation of the belt of black-owned farms and homesteads that stretched for two miles from Georgetown in the south, along present Hydraulic, Rio, Woodburn, and Earlysville roads north to Cartersburg and Allentown.

The Church

At the heart of the Hydraulic Mills-Union Ridge community was the Union Ridge Baptist Church, founded as the Salem Church two years after the Civil War ended. The establishment of independent churches was frequently the first activity of newly-freed people. Berkeley Bullock and Albert Wheeler were among Union Ridge’s trustees and Jesse Scott Sammons was the church secretary. In 1876 an African-American preacher, George Crawford, one of the six men who had bought land as a group, gave the congregation a quarter-acre for a church building. The Union Ridge Church still stands today as the home of an active Baptist congregation.

The School

The Hydraulic Mills-Union Ridge community is an extraordinary example of African-American belief in the importance of education. Its early school evolved into the Albemarle Training School, the first black high school in Albemarle County and a magnet for African-American students outside the city of Charlottesville. Jesse S. Sammons, Rives Minor, and Hugh Carr’s daughter Mary Carr Greer were all important figures in this development, as teachers and principals. Sammons’s and Minor’s daughters, Albert Wheeler’s son Thomas, and others in the community also became teachers. Like the Jefferson School in Charlottesville, the Union Ridge/Albemarle Training School paved the way for many African Americans who aspired to full participation in the American dream.

Leaving the Land

In the early years of the twentieth century, limited opportunities in the Jim Crow south caused some Union Ridge residents to begin to migrate northwards and by the 1940s the encroachments of an expanding suburban Charlottesville started to alter the makeup of the community. Only remnants of the once-thriving African-American community survive today, some of them in the direct path of the proposed Route 29/Western Bypass.

Community Residents

The Hydraulic Mills / Union Ridge community had many prominent members, including the following individuals:

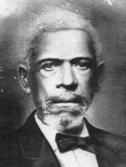

Berkeley Bullock

Berkeley Bullock (c1835-1908) purchased a 35-acre farm between the properties of Hugh Carr and Jesse S. Sammons. He was a principal founder of what became Union Ridge Baptist Church. In the 1890s he moved into Charlottesville, where he owned and operated a popular restaurant at Union Station and engaged in the wood, coal, and ice business. He was described as “one of the pioneer businessmen of the city.”

Photo Courtesy of Corks and Curls, 1889-1890. University of Virginia Library.

Hugh Carr

Hugh Carr (c1840-1914) was born in slavery on the plantation of R. W. Wingfield of Woodlands. He led a life in freedom that exemplifies the struggle and accomplishments of many former slaves in the post-bellum Hydraulic Mills area. At first renting farmland on shares, he began purchasing property in 1870 and left over a hundred acres to his heirs at his death. Carr and his second wife, Texie Mae Hawkins, raised seven children, instilling in them the value of an education, something Carr never had. His children became teachers and community leaders, most notably his daughter Mary Louise Carr Greer. Hugh Carr’s River View farm remained in the family for a hundred years and is now the Ivy Creek Natural Area.

Photo Courtesy of the Ivy Creek Foundation. To visit their site with more information, click here.

Moses Gillette

Moses Gillette (1837-after 1920) was the son of Martha and Moses Gillette, a cooper at the Hydraulic Mills who had been born in slavery at Monticello and trained in his trade there. The younger Moses Gillette purchased ten acres of land across the Rivanna River from the mills in 1875. There he farmed and raised a very large family.

Photo courtesy of the Gillette Family.

Albert Wheeler

Albert Wheeler (c1826-after 1900), who was born in slavery, practiced his blacksmithing trade in freedom, first in North Garden and then at the Hydraulic Mills. He was a trustee of Union Ridge Baptist church. In 1872 Wheeler bought a 32-acre farm close to the mills on the east side of Hugh Carr’s River View farm. There he and his wife, Wilmina, raised six children, one of whom became a teacher.

Tinsley Woodfolk

Rev. Tinsley Woodfolk (1848-1907), born in slavery, was a prominent Baptist minister. He founded three churches in Albemarle County, including Pleasant Grove Baptist Church established in Earlysville before 1874. In 1869, he married Letitia Allen (1852-1923), who had been enslaved on the Burnley plantation that adjoined four contiguous lots that Tinsley and other family members bought in 1873 in the Cartersburg section of the Hydraulic Mills community. Tinsley and Letitia Woodfolk had ten children; some of their descendants remain in the Charlottesville area.

Mary Carr Greer

Mary Carr Greer (1894-1973) and Conly Garfield Greer (1884-1956) are prime examples the role education played in the lives of freed slaves and their children. Mary, eldest child of Hugh and Texie Carr, attended Union Ridge Graded School and was a teacher and then principal of the Albemarle Training School. She oversaw its development into a 4-year accredited institution offering a curriculum comparable to white high schools. Mary Carr Greer Elementary School on Lambs Road is named in her honor.

Photo courtesy of the Ivy Creek Foundation. To visit their site to learn more about her and her family, click here.

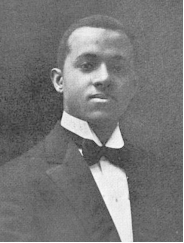

Conly Garfield Greer

In 1914, Mary’s husband, Conley Greer, a fellow graduate of the Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute (now Virginia State), became Albemarle County’s first African-American extension agent. He made River View a model farm and taught African-American farmers and 4-H youth modern farming techniques. Now the Ivy Creek Natural Area, the farm is a Virginia African-American Heritage site in honor of a century of Carr-Greer history.

Conly Greer. Source: Ivy Creek Foundation Website, Click here for more information about him.

Dr. John A. Jackson

Dr. John A. Jackson (1888-1957), educated at Howard University School of Dentistry, was a dentist in Charlottesville and Lynchburg and served as the first Secretary-Treasurer of the National Dental Association. He was instrumental in the development of Washington Park in Charlottesville, where he resided and had his office. He also owned an 82-acre farm adjacent to Jesse S. Sammons; his father, Andrew W. Jackson, had purchased it in 1918. Here Boy Scouts camped and learned to cultivate a garden, and a swimming pool provided a recreational opportunity for African-American children in Albemarle County. Dr. Jackson’s wife, Otelia Love Jackson, served on the Charlottesville Welfare Board and was active in many civic groups.

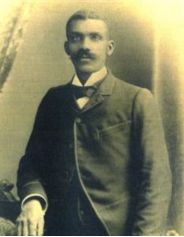

Rives Minor

Rives Minor (1856-1926), showed remarkable determination in achieving an education and sharing his knowledge. He attended the Freedmen’s school in Charlottesville and Storer College in Harper’s Ferry. He taught for thirty years, many of them at the Union Ridge Graded School; he was its principal after the death of Jesse S. Sammons. Through inheritance and purchase he accumulated over sixty acres of land close to Union Ridge Baptist Church. His daughter Asalie Minor Preston was a noted educator in Albemarle County, including at the Albemarle Training School. In 1982, she endowed the Minor-Preston Educational Fund that to this day supports and recognizes worthy public school students in the Charlottesville-Albemarle community and awards scholarships to graduating seniors.

Photo courtesy of the Minor Preston Educational Fund.

Horace Solomon

Horace Solomon (1858-1927) whose family had been enslaved in the Hydraulic Mills area, farmed on shares in the first years after Emancipation. Soon he was able to buy his own small farm in the Georgetown section of the Hydraulic Mills-Union Ridge community. He and his wife, Fannie Harris (1862-1943), raised fifteen children and some of their descendants still live in the area.

The following list includes many of the families who lived in the Hydraulic Mills / Union Ridge community: Allen Armstead Beck Blakey Bowles Brown Bullock Burkett Byers Carey Carr Carter Clark Clayton Coleman Coles Crawford Dawson Dickerson Douglas Estes Flannagan Fleming Gentry Gibbons Gillette Gilmer Gilmore Givens Gofney Hare Harris Hawkins Henderson Holmes Howard Hughes Irving Jackson Jefferson Johnson Jones Kennedy Key Knox Lincoln Logan Magruder McKenny Mills Minor Nicholas Overton Piper Preston Ragland Rives Sammons Shepherd Smith Solomon Sorrel Southall Spinner Sullivan Thomas Tinsley Tyler Walker Watson Wheeler White Williams Winn Winston Wood Woodfolk Young

A Selection of Archival Sources Used in this Research

Public records for Albemarle County: birth and death records, censuses (population and non-population), chancery court cases, deed books, land and personal property tax records, marriage records, will books

Newspaper articles in the Charlottesville Chronicle, Daily Progress, and Jeffersonian Republican; Richmond Daily Dispatch and Planet; Roanoke Daily Times

“A Short History of Ayteesse,” Albemarle Training School Yearbook, 1948, University of Virginia Library Acc. No. 10176

Samuel T. Bitting, Rural Land Ownership Among the Negroes of Virginia [University of Virginia Phelps-Stokes Fellowship Paper], 1915

Philena Carkin Reminiscences, 1866-1902, Philena Carkin Papers, University of Virginia Library

Chataigne’s Virginia Gazetteer, 1888-1889

Corks and Curls [University of Virginia], no. 4 (1889-1890), 132-133

Getting Word Oral History Project files and digital archive, Monticello

Hill’s directories of the city of Charlottesville

Journal of Negro History, 14, no. 3 (1929), 263-264

Journal of the National Medical Association, 25, no. 1 (1933), 35-36

Union Ridge Baptist Church manuscript history, 18 Apr. 2004

Background on the Hydraulic Mills Community, courtesy of the Ivy Creek Foundation.